New Low-Cost Surgical Tool Could Help Patients in Third World

Xenoscope, an inexpensive laparoscope for minimally invasive surgery, was born of an iPhone flashlight

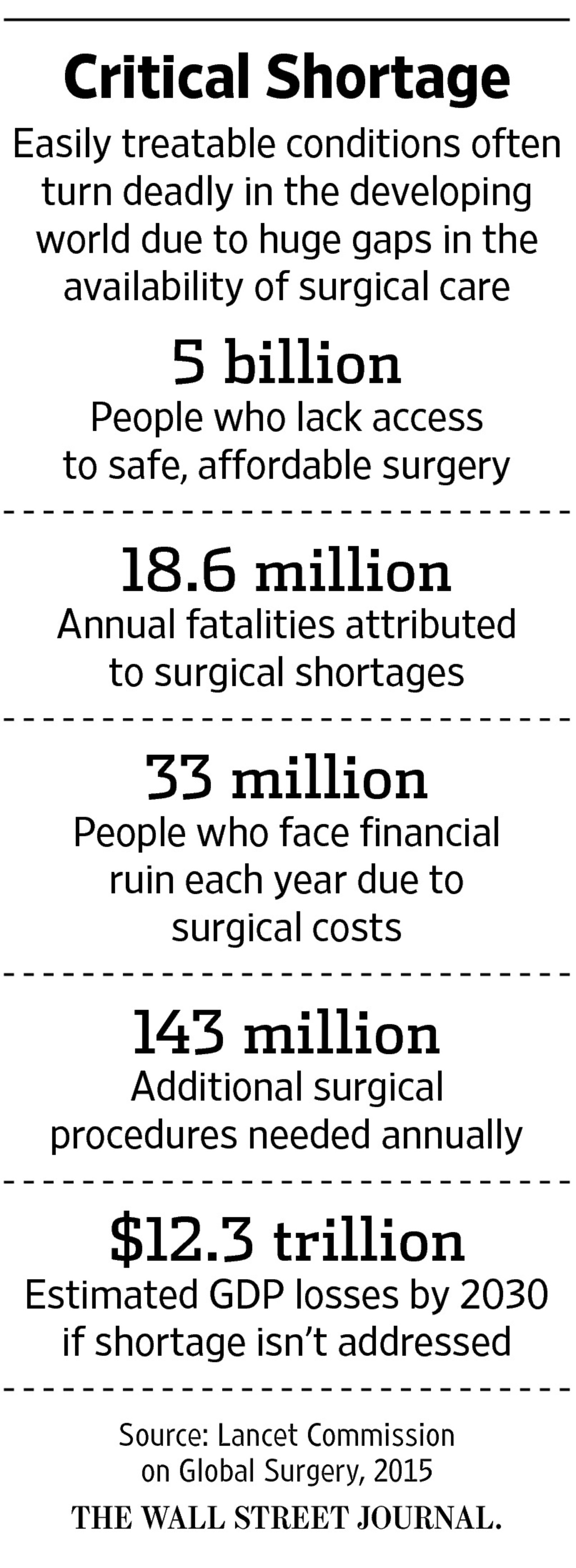

Two-thirds of the world’s population—some five billion people—lack access to safe, affordable surgical care.

An $85 device conceived in a sock drawer could help change that.

John Langell, a surgeon who runs the University of Utah’s Center for Medical Innovation, had the idea when he was called in for an emergency late one night and used his iPhone flashlight to look for clothes without waking his wife. “I thought, ‘Wow, this is as bright as a laparoscope,’ ” he recalls.

Dr. Langell passed the thought on to students in his bio-innovation class who were looking for a project: Why not build a low-cost laparoscope using cellphone parts and bring minimally invasive surgery to regions of the world that can’t afford it?

-

The Joint Fight Against Pancreatic Cancer

Scientists and doctors from disparate fields join forces to find a breakthrough for the tough-to-treat disease.

Click to Read Story

-

The Revolution in EMS Care

Ambulance crews shed 'horizontal taxicabs’ image thanks to new technology, life-saving techniques and missions.

Click to Read Story

-

Doctors Dig for More Data About Patients

In effort to predict health problems, doctors are looking at a broad range of personal information about patients

Click to Read Story

-

Advertisement

-

New Gadgets Could Give the Remote House Call a Boost

Diagnostic gadgets such as the Tyto and MedWand let patients do tests at home, send the information to a doctor.

Click to Read Story

-

The Key to Health-Care Innovation in Developing Nations

The success in developing new, innovative products depends on understanding the conditions and resources of the local community.

Click to Read Story

-

The Potentially Deadly Danger of Medication Errors for Children

Pediatric patients are vulnerable to mistakes made in how much medicine to give and when to give it.

Click to Read Story

-

Advertisement

Innovations in Health Care

Journal Report

- Insights from The Experts

- Read more at WSJ.com/HealthReport

More in Innovations in Health Care

A laparoscope is a thin tube with a tiny camera on the end that allows doctors to perform surgery inside a patient’s belly by means of a few small holes rather than a large incision. Surgeons can see a magnified image of the abdominal cavity and watch what they are doing on an external video screen.

Such tools typically cost more than $20,000. And additional equipment —including an image-processing tower and a high-definition video screen—requires a capital investment of as much as $700,000. Most systems are sold with an annual service contract that adds thousands of dollars more.

The alternative that Dr. Langell’s team devised—the Xenoscope—costs about $85 to produce. There’s no need for a large image-processing tower or video screen. Surgeons can watch the video feed on an ordinary laptop—even a smartphone—which can also provide all the power the laparoscope needs for up to eight hours. That will allow doctors to perform minimally invasive surgery virtually anywhere—even without a hospital or reliable electricity.

Xenocor Inc., the company the team founded, expects to sell the devices for $300 to $500, with no need for a capital investment or service contract.

“It’s so inexpensive, if you break it, you just throw it away,” Dr. Langell says.

The Xenoscope is part of a new wave of ultra-low-cost medical devices being designed, mostly by graduate students, to work in parts of the world where money is scarce, electricity unstable and clean water isn’t assured. Universities are enlisting engineers, scientists, designers and business students to identify health-care-delivery problems and to devise low-cost, practical solutions, many of which address a critical need for surgical services.

Lack of basic surgical care in many middle- and lower-income countries is responsible for more than 18 million deaths a year from burst appendixes, diseased gallbladders, tumors, traumas and other treatable conditions, according to estimates from the Lancet Commission on Global Surgery, a multinational effort to address the issue. The World Health Organization and World Bank identify improving surgical capabilities as an essential step to raising health and economic standards around the world.

“You’re going to see a lot more companies tailoring products for low-income markets,” says John G. Meara, co-chair of the Lancet Commission and director of the program in Global Surgery and Social Change at Harvard Medical School. Lowering surgical equipment costs, building needed infrastructure and training more medical workers are all critical, he says.

A greater need

Minimally invasive surgery has become standard for many conditions in developed countries, largely because it gives patients faster recoveries, fewer hospital stays, less pain and a lower risk of infection than open surgery. Those same advantages are even more critical in poor countries, where hospital beds are scarce and family breadwinners can’t take weeks off from work while large incisions heal.

Yet only 18% of the world’s population has access to laparoscopic surgery, the Lancet Commission reports.

In Mongolia, where nomadic herders have a high rate of gallbladder disease, health officials have clamored for what some patients call “the surgery with the little holes,” says Ray Price, co-chair of global surgery for the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, or Sages. Dr. Price, who has taught laparoscopic surgery in Mongolia since 2005, plans to demonstrate the Xenoscope there for gallbladder removal this week.

As simple as Dr. Langell’s idea sounded, getting an inexpensive cellphone camera to take high-quality images in the dark, wet confines of the abdominal cavity posed a number of technical challenges that off-the-shelf solutions sourced overseas didn't handle well.

“Typically, a smartphone sensor is capturing images of a person or a mountain—not something five centimeters away,” says Lane Brooks, a pioneer in digital-camera design and miniaturization who was recruited to the team.

Mr. Brooks concluded that rather than use a camera from an off-the-shelf smartphone system, the team needed to create its own custom optics and image processor. But the team was able to buy other key parts, including the image sensor and LED light, very inexpensively because the huge demand for cellphones has made them cheap commodities.

One early engineering problem was a one- to two-second buffering delay in seeing the image on the screen—a potentially dangerous time lag during surgery. Mr. Brooks designed a custom image-processing pipeline that eliminated the need for buffering. Another issue: Light from the LED leaked into the lens, bleaching out the image.

“We became like plumbers finding each source of the light leaking, and developing ways to block it,” he says.

With those obstacles overcome, Dr. Langell used the Xenoscope last summer to perform minimally invasive surgery on a pig. All went well until he used an electrical cauterizing device to finish the operation, and the electromagnetic interference ruined the video image. That sent the team back to the drawing board to find substitute materials for the tube and ways to shield the sensor and data cables.

By late fall, the team retested the Xenoscope inside turkey carcasses left over from Thanksgiving. Dr. Langell says he was “blown away by the image quality—it’s as good as any laparoscope I’ve used.”

In May, surgeons in India performed a first human test of the Xenoscope in an operation removing fallopian tubes. Drs. Langell and Price observed the procedure and visited the patient at her home the next day. “She was up, mobile and had zero pain,” says Dr. Langell.

NASA interest

Surgeons from Nigeria, Ghana, China and Morocco have expressed interest in the Xenoscope. (So has NASA, which envisions someday doing surgery in space.)

There are still hurdles ahead. The team has asked the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Union to designate the Xenoscope as substantially equivalent to existing technology, which means it could forego lengthy clinical trials. Also, Dr. Langell wants to wait until the FDA and EU regulators are satisfied before the company rolls out the Xenoscope more broadly.

Xenocor needs to raise $5 million in Series A funding to gear up manufacturing. It hopes to form partnerships with companies in developing countries that can assemble and distribute the Xenoscope locally. It also hopes to market the tool in the U.S. as a single-use device, eliminating the threat of infection posed by laparoscopes.

Dr. Price, who practices at Intermountain Healthcare in Salt Lake City, and colleagues at three nearby hospitals have proposed a trial comparing the quality of the Xenoscope to traditional laparoscopic equipment. If an $85 device does perform just as well as one that costs thousands of dollars, Dr. Price says, “could it drive down the cost of minimally invasive surgery and disrupt our own high-price health care? I hope so.”

Ms. Beck is a Wall Street Journal senior editor in New York. She can be reached at melinda.beck@wsj.com.

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20170301/030117uberdrivervideo1/030117uberdrivervideo1_167x94.jpg]](./wsj_xenocor_files/030117uberdrivervideo1_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20170228/022817trump3min/022817trump3min_167x94.jpg]](./wsj_xenocor_files/022817trump3min_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20170301/030117mountetna/030117mountetna_167x94.jpg]](./wsj_xenocor_files/030117mountetna_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20170228/030117switch/030117switch_167x94.jpg]](./wsj_xenocor_files/030117switch_167x94.jpg)

![[https://m.wsj.net/video/20170301/030117htcvive/030117htcvive_167x94.jpg]](./wsj_xenocor_files/030117htcvive_167x94.jpg)